Post

Life after faith - how do atheists ground morals?

It was an otherwise unsuspicious church service. The youth pastor asked for all the teenage boys to follow him into a private meeting room. Once we were all situated, he asked in a hushed tone “did you know that guys who masturbate start growing hair on their hands?” The room was quickly transformed into a wild frenzy as dozens of panicked young boys began closely examining their hands. After about few seconds, the dust settled, and all of us realized we had been tricked. The room was filled with nervous laughter. And then we listened to a sermon that taught us masturbation and premarital sex was a sin, because God said so.

An hour later, when the rest of the group rejoined the adults in the large sanctuary, the nerds among us found a secluded classroom and began to discuss the issue of sin and sexuality. We could understand why God would want to make murder or robbery a sin, after all, it harms the person who is getting murdered or robbed. But we couldn’t, for the life of us, figure out why God would have made most sexual acts a sin. One of my friends said it was because sex creates a supernatural spiritual connection, and that it can only happen with one person. Another friend said it was because it’s selfish and gives you too much pleasure. But all of us thought there had to be a reason to forbid it, God wouldn’t just designate some random act as an evil, for no good reason!

Would he?

It was then I first encountered that difficult question: what makes something good or evil? Is it the consequence of the action? Is it because God said so? Why would God designate one thing as good, and another as evil? Whatever the answers are, the question is not an easy one. There are thousands of philosophy books that deal with ethics and most are notoriously difficult for the average person to understand. So my goal with this post is to make things as simple as possible, and very practical, even if that means oversimplifying a really complicated topic that still sees much academic debate and disagreement.

1. A MISTAKE WE MAKE WHEN TALKING ABOUT ETHICS

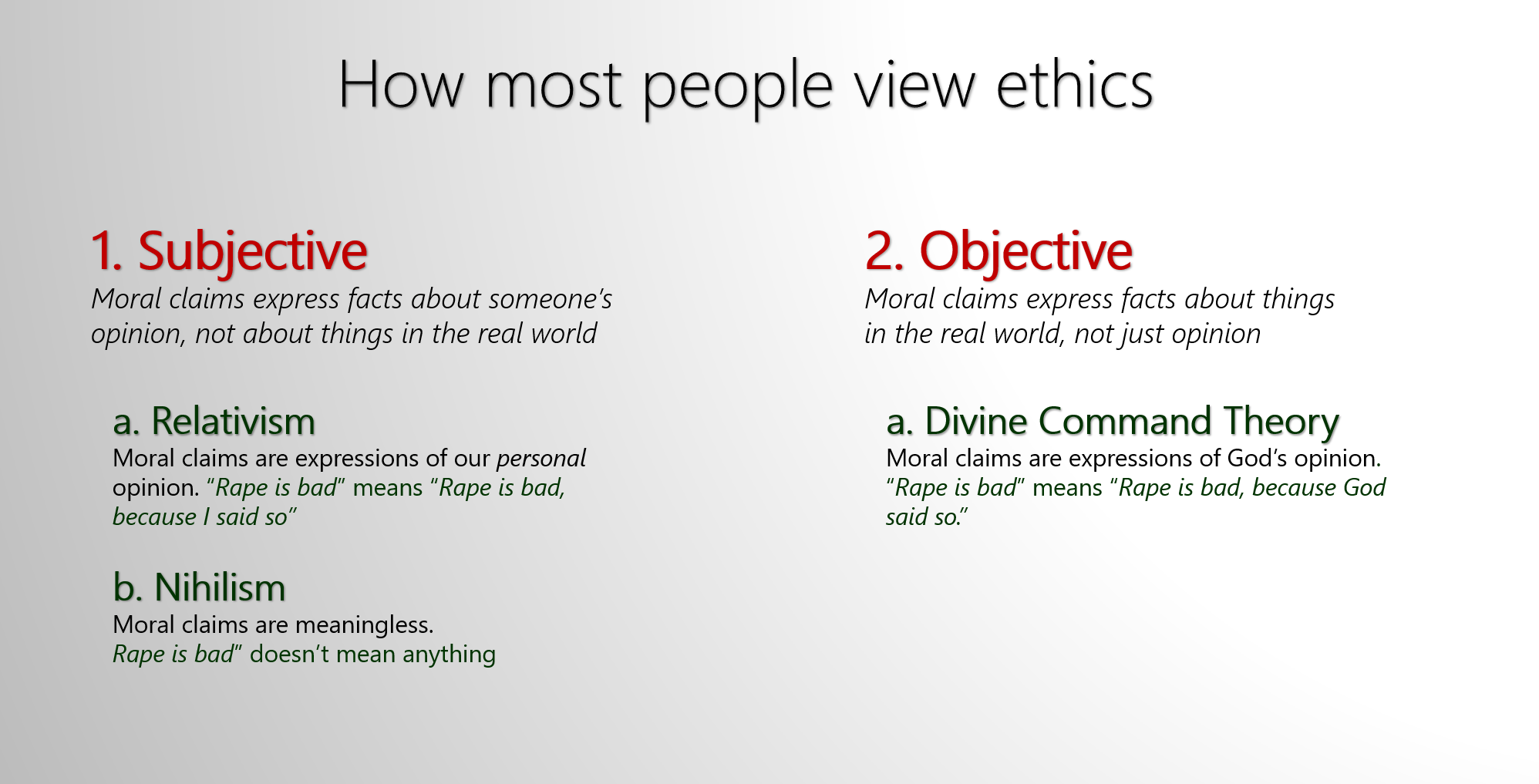

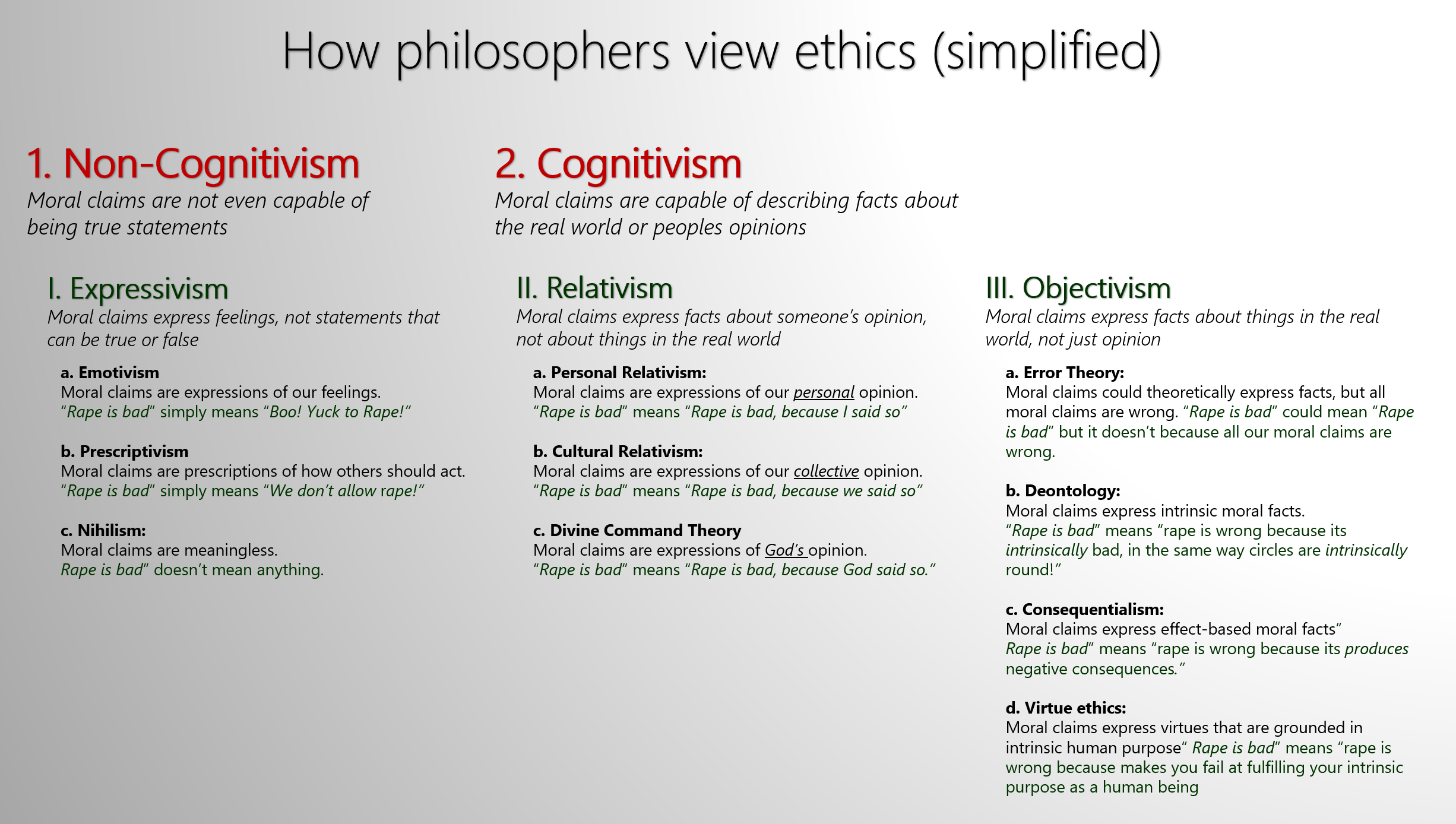

From an early age I discovered that it’s very difficult to talk about ethics because people hold preconceived notions that are faulty. So before we dive into how atheists/agnostics can ground ethics without God, lets take an eraser to the chalkboard that is this conversation. Lets be aware of a big mistake that can make this conversation impossible: viewing ethics as a false dichotomy.About five years ago, I was invited to a large Christmas party. There was food, games, prizes, and pretty girls (yes, my then future wife was there, and she was the prettiest). And yet, I spent 2 hours of this party discussing ethics with someone I had just met. He believed ethics could exist without God, and I tried to disabuse him from his error. Irrespective of how much I tried, I could not get him to see things my way. This was because I viewed ethics as a false dichotomy: (a) either moral standards come from God, or (b) they were mere opinions and philosophically ungrounded.

And yet, things aren’t so simple. When I tried to argue “if you’re don’t believe in A, by definition you must believe in B,” I was completely wrong and naïve. The largest survey of philosophers has indicated that: 85.4% of philosophers do not believe in a personal God, and yet only 27.7% reject the concept of objective moral values. This means the vast majority of PhD level philosophers are neither (a) theists (b) nor ethical nihilists/relativists.

I was not prepared for this. I had only extrapolated the logical conclusion of my views upon other people, I had never sincerely considered things from their perspective, only “what I would think, if I was in their shoes.”

Turns out that throughout the ages thousands of philosophers have written hundreds of thousands of pages trying to comprehend morality. There is a whole field of philosophy, metaethics, that aims to simply understand what ethical statements really are. What does ‘good’ and ‘evil’ even mean? How are they defined? Where do they come from? There is a second field of philosophy, normative ethics, that aims to understand the standards of ethical actions and figure out what kinds of things are right and wrong.

I created the following chart to show a simplified breakdown of the ethical situation in philosophy, to better present the actual choices people have. There are certainly more options than these 10 presented, but lets note that there are more than the 2 choices most people assume. Please click for a larger view.

2. A SHORT CRITIQUE OF THEISTIC ETHICS

a. Do we need God to have objective moral standards?

Most believers say that objective moral values can only exist if there is a God. Though having had many discussions with Christian friends, I've not heard a good logical reason why this has to be the case. Now it’s true that some propositions are simply axiomatic, meaning they are true without requiring a reason or justification; for example, the sentence: “Drawing four right angles is the only way to make a square.” It is true because its logically impossible for it to be false. Because a square, by definition has four angles, it’s self-evident that you can’t make a square with more or fewer angles.Is the necessity of God for objective moral values also axiomatic? No, it’s not. The sentence: “God is the only possible way to derive objective moral values” is not a self-evident truth. It is possible for this sentence to be false, and in fact, we can demonstrate that it is. To do that, we must simply provide one alternative account of objective moral values. Do such accounts exist? Absolutely! Here is just one example: objective moral standards “just exist – without explanation” in the same exact way theists propose that God “just exists without explanation.”

Think that is strange? Maybe. But the mathematical truth of 1+1=2 just exists as a fact, and while that’s really strange, it’s no less true. It’s even more strange to imagine that an intelligent being like God can “just exist” without being created, so why exclude something far simpler, like a set of moral laws? (“But who made those laws?” Well, who made God? “But God has always existed!” Then perhaps moral laws have always existed?). In the end, because there is nothing logically contradictory about moral laws “just existing” we can surmise that it’s a real possibility. Thus the statement “God is the only possible way to derive objective moral values” is demonstrably false.

So why do people say God is required? There are two reasons, (i) moral epistemology and (ii) moral ontology.

(i) Some think God is necessary because we cannot learn about moral values (moral epistemology) without God’s revelation. But that doesn’t make sense. Just because I don’t have a math teacher doesn’t make mathematics disappear. If I have no one to reveal to me that 1+1=2 is true, that won’t make it false! If there was nobody to teach us that drinking poison was bad for our well-being, it would still be true that drinking poising would kill us. In the same way, if there are moral facts, but nobody to teach us what they are, those facts don’t just disappear. It seems, therefore, that God as moral teacher, is not required for the existence of moral truths, just like math teachers are not required for the existence of math facts.

(ii) Others might say that God is required not as a source of knowledge about moral facts, but as the source of those facts themselves (moral ontology). Without God, they argue, objective moral standards cannot be created, because “moral laws require a moral law giver.” But is this really the case? Why should objective moral laws require a moral law giver? Do mathematical laws require a mathematical law-giver? Is the proposition “1+1=2” false unless a math-law-giver says its true? Not at all! Is the law of non-contradiction (“X can’t be both X and not-X”) only true because a logical-law giver said so? Again, no. So why then should moral law require a moral law giver? In fact, simply saying that a particular law requires a law-giver, necessarily means that this law cannot be objective but must be subjective. If it’s only grounded on the law giver, it must be subject to the law giver. It must be contingent on his/her choices, and he or she could give any law that he wants to.

b. Is it even possible for God to be to source of objective moral standards?

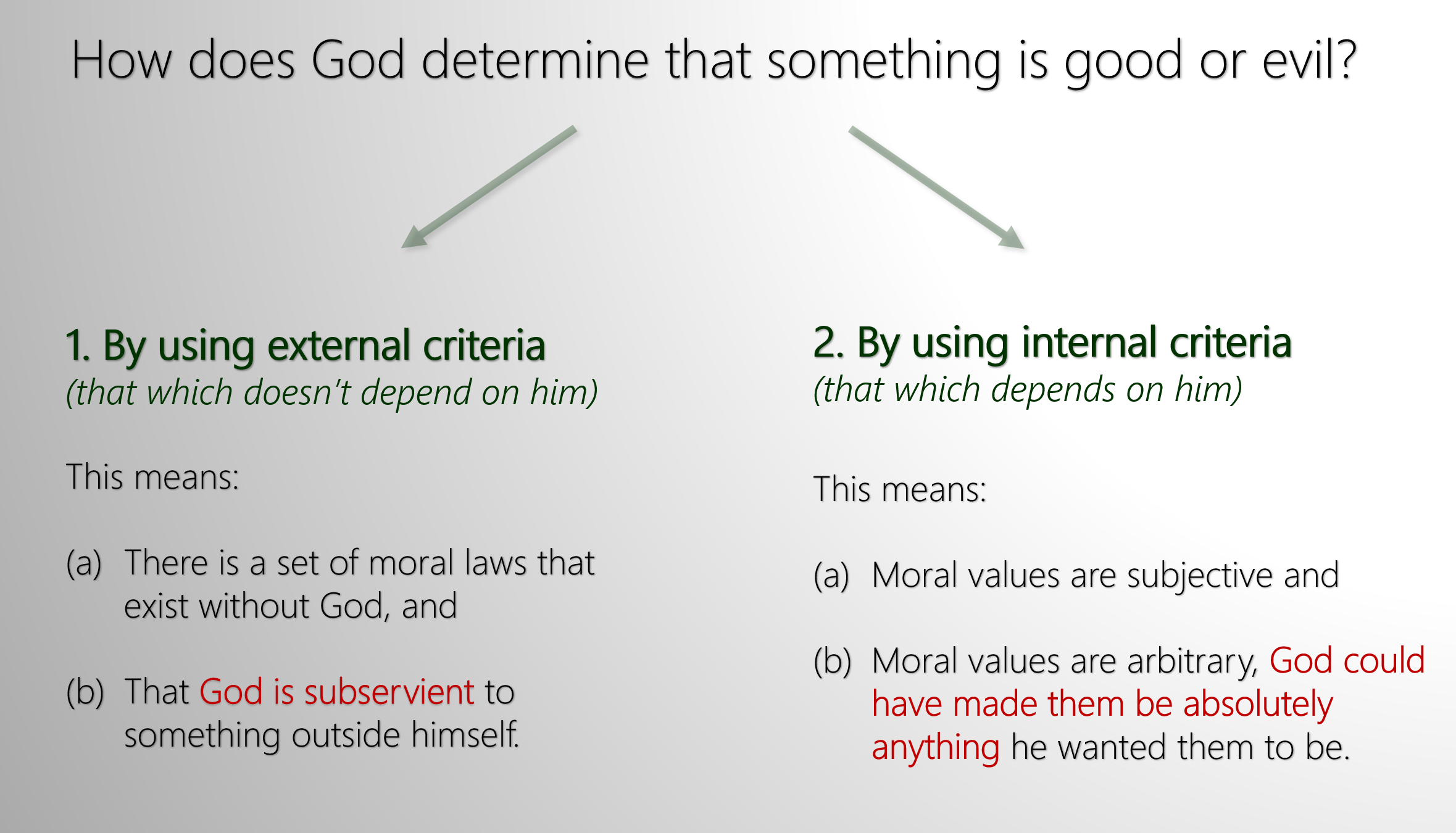

If you think the problem above is difficult to overcome, trying to ground objective moral values in God's commands has an ever greater problem, the Euthyphro dilemma. This is a question about how God determines what things are good and evil. The only two possible options are: (a) God produces moral standards from within himself or (b) he obtains them from outside of himself. If we answer with A and say God determines good and evil from within himself, then it follows that there are no objective moral standards, they are all subjective to God, and therefore arbitrary. God could easily say "rape is good" and "kindness is evil" and we would have no way of knowing otherwise. Yet, if the answer is B, God obtains moral standards from outside himself, then this means there is a source of moral standards apart from God, and it is a moral standard that even God must obey. This means God is subservient to something else.The image below presents an outline of this serious problem.

Christian theologians try to overcome this problem by saying that God’s nature is what grounds his ethical choices. They say Gods nature and character is intrinsically good, and that God determines whether a command is good or bad, by looking inward at his nature. This answer misunderstands the problem and only pushes Euthyphro’s dilemma one step backwards. We can step back and still ask the same question: how can we know Gods nature is good? Are God’s character traits considered ‘good’ as a result of fitting some external criteria of what is good and evil? Or are those character traits considered ‘good’ only as a result of God having them? (If Satan’s character traits were given to God, would they too become good, simply because they are now Gods?)

So we still have the same dilemma. If you answer with: (a) God determines it by looking outward, it logically follows that there exists a moral standard outside of God that he has to obey. This moral standard is “more God” than God. If you answer with: (b) God determines it by looking inward, we can ask: how does God determine that this set of character traits are good, but not another set? What internal criteria does he use? If God uses his nature, to determine if his nature is good, is that not circular and arbitrary?

As an analogy, assume that I invented a ruler/measuring stick that uses a newly invented unit called “zibs” instead of inches or centimeters. If this is the case, then the only way for us to know that “3 zibs” is really “3 zibs” is because I measured it with this new ruler! Isn’t that completely arbitrary? We could make any kind of measuring stick, and use it to measure itself, but that is an arbitrary measurement! It doesn’t mean anything more than “if we define a zib as this, then this is a zib.” But there is no real, unchanging, objective thing called a zib, its just something we made up!

At the end of the day, grounding ethics on God’s moral edicts is very difficult and filled with many paradoxes and problems. I think there is a much better way, that is both more pragmatic and more logical.

3. A SHORT PRESENTATION OF NONTHEISTIC ETHICS

a. What is good & evil? (Moral Ontology)

Our first question is a question of moral ontology, or what do the concepts of good and evil really mean? When it comes to ethical or moral statements, according to my naturalistic view, I define good and evil as two types of 'states of affairs' that correlate to sensory experiences by cognizant beings. Rocks and trucks cannot be the recipients or agents of moral good and moral evil, only sentient beings that are capable of experience:- Moral Good: the state of affairs in which a sentient being attains well-being and flourishing.

- Moral Evil: the state of affairs in which a sentient being attains ill-being and harm, or is derived of some moral good.

The specific actions may change, as they depend on one’s nature, but the ultimate consequences can be judged objectively. For example, some plants may need to be submerged in water year round, others watered daily, and some never at all. Yet, each of them has a specific set of circumstances, which are an objective fact for that plant, that produce the state of affairs we call health. Just because each plant requires a different set of actions to produce the consequence of health, doesn’t mean everything is now simply a matter of opinion. It’s not an opinion. We can take a microscope to the plant, and objectively evaluate its status. We can ask, “has watering helped or harmed this plant?” And we can know the answer as a fact, not an opinion.

Objective moral judgments are not a series of meticulously specific laws that apply to every single action, situation, and person for all time, but rather objective assessments we can make about the ultimate consequences. (For example the specific command that “lying is always bad” seems to prevent you from lying to a group of Nazis, in order to save Jewish lives. On the other hand the assessment that “harm is a bad thing” might encourage you to lie in order to prevent the Jews from being harmed.)

So how do we figure out what things are good for what beings? We will discuss this in section C below, but first we need to understand the complexity of moral situations.

b. How does an ethical decision work? (Moral Taxonomy)

When it comes to describing an ethical situation, I would describe it as having at least three parts which are not reducible to one. In every case when I want to understand a moral scenario, I need to know at least three things about it. These are(i) moral intentions, which produce

(ii) moral actions, which in turn result in

(iii) moral consequences.

In other words, first someone desires to kill you, then they stab you, finally this results in your death. Each of these steps in the chain is vital to narrating the whole story, and we should do our best to avoid simply calling the whole chain “good” or “evil” because there are instances where its composed of different parts.First, we can have scenarios where good intentions produce evils. My intentions can be good, while my actions and the resulting consequences can evil. For example, I may believe that pressing a blue button will help all people, but instead it launches a nuclear weapon that kills them. The consequences instantiated by my action were truly evil, but my intentions were sincerely good. Of course these good intention don’t justify the consequence; it is undeniably evil. Yet, in this scenario, the problem was a disconnect between my desires and the outcomes, I am to blame for knowing the wrong information about the button, not for desiring to kill everyone.

Second, we can have situations where evil intentions produce good. Imagine a sadistic person who wishes to cause severe pain and death to everyone on this planet, and so he clicks a red button. hoping to instantiate evil. Yet, this button simple causes millions of balloons to be sent to children in hospitals worldwide, making them quite happy. He inadvertently caused a “good” action, one that he did not intend. It would be far too simple to say “he did a good thing” for the whole story shows us his intentions were evil, and the good outcome is an accident.

Finally, we can also imagine scenarios where some parts of our moral chain are missing. For example, someone who is sleep walking and (i) without intention causes (ii) an action that results in (iii) another person’s harm. Or perhaps a ghost who (i) intends to harm innocent people but (ii) cannot act in a way that (iii) causes any kind of outcome or consequence.

Examples like these demonstrate that while terms like “good” and “evil” are appropriate words to describe moral situations, they should be used carefully and not be overly simplified. Knowing the full chain of events, we can far better grasp the whole moral situation than simply shouting “evil!” or “good!”

c. How do we know what things are good? (Moral Epistemology)

This is the question of moral epistemology, or how can we know what things are good? In my opinion, this is an easy question to answer, at least at a theoretical level, but can be a bit more difficult in the real world. Simply put, our goal is to discover what is “good,” or what is “the state of affairs in which a specific sentient being attains ultimate well-being and flourishing?”Ideally, we would take each sentient being, put them into a theoretical laboratory, subject them to every single possible action/consequence, and then see which of these things result in well-being and which result in ill-being (biologically and psychologically). This would provide us with a comprehensive answer. Yet, we neither have the time nor resources to do this. Besides, experimentally subjecting people to every possible bad thing, is… well, bad.

So what’s our alternative? We use the very best of our knowledge of human nature, accumulated over thousands of years. We ask our fellows, “what kinds of things will harm/benefit you?” because most people can accurately gauge many things through introspection. And finally, we experiment, we try new things, we observe, and we learn.

Let’s revisit the mythical story of Adam and Eve. Before anyone had ever been poked with a sharp object, how could Eve have known that poking Adam with a needle would cause harm and pain? Unless God magically implanted that knowledge into her mind, the only way she could have known is by poking herself or Adam and observing the reaction. Before that, nobody could know what would happen.

At the end of the day, its that simple, but also that difficult. It leaves us in the position of ethical agnosticism regarding some future outcomes, especially concerning new things we have never encountered. We don’t know the exact consequences of some future actions on certain people. But it also gives us an objective methodology for assessing any actions that have been committed in the past. We can evaluate the motivation, action, and consequences of actions in the past, and apply what we learn to our decision making.

Recall that moral scenarios includes these three parts: (i) moral intentions, (ii) moral actions, & (iii) moral consequences. Using this trilemma, we can summarize the situation in moral epistemology as follows:

(i) Moral intentions: we can evaluate intentions by asking introspective questions, like “why did I/you intend to do this action?"

(ii) Moral actions: We can evaluate actions by examining the direct casual outcomes they produce

(ii) Moral consequences: We can understand outcomes because they correspond to the mental and physical well-being of the subject.

e Why should we do things that are good? (Moral Motivation)

Alas, we have come to the hardest question. The question of moral motivation, or what kinds of things compel us to act a particular way. Hume once called this the “is-ought” problem, and to this day, it’s never been adequately answered. If we all agree that something is good, why ought we do that thing? Sure, it’s good. But, so what?Let’s imagine that God was real, appeared before me, and then commanded me to give all my money to the rich because “it is a morally good thing to do.”

So what? Why should I care?

Even if I agree, and say “okay God, that is indeed a morally good thing to do” why should I actually do it? What could God or anyone else say to motivate me? Why is it right to do a good thing? What compels me to do good?

- If God says “jump,” I can ask “why?”

- If God says “because jumping is good” I can ask “why is it good?”

- If God says “because I said so” I can ask “why does that matter?”

- If God says “just do it, because it’s good” I am back to asking “why”?

- Just because something is good, doesn't give us motivation to do it.

- The only obligatory motivation for repentance is to be saved from pain, and enjoy eternity.

- The only obligatory motivation for avoiding sin is to avoid the harm caused by sin & hell.

- The only obligatory motivation for good deeds is to be loved/rewarded by God & people.

- The only obligatory motivation for loving God, is the personal fulfillment experienced.

In fact there are all kinds of self-interested motivators, and without them action is impossible. They include being rewarded with (a) physical possessions, (b) pleasant mental/spiritual experiences, (c) respect/affection from others (d) the internal mental experience of doing such a good deed, causing others happiness, or even of doing something good, just for its own sake without expecting a reward.

If there is nothing at all to motivate a person to perform some moral action, there will be no action, unless it’s random and unintentional. This really strips the issue of ethics to its core and exposes the greatest fear of most religious people: If there is no God who will punish/reward you, what guarantee do I have that you will continue to do good to me?

There is no magical guarantee that I can offer, and that seems frightening.

Yet fear not, most human beings, by nature are social and altruistic creatures, we are wired to create bonds with others and flourish best when working cooperatively together. We achieve our own personal flourishing best when we promote flourishing in others. We satisfy our own safety best when we create societies where violence is illegal, and when we don’t act violently towards others. We promote our own good, when we treat others in a way that is good. As Jesus said, “he who lives by the sword, dies by the sword” and so “do to others what you would want them to do to you.”

Even Jesus appealed to self-interested desire to motivate listeners to act according to his greatest ethical commandment. There is no reason atheists can’t do the same.

Comments (27)