Post

Why I changed - Biblical studies scares my buddies

This is the conclusion of a series (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4). I have taken a journey. From a zealous fundamentalist with dogmatic views, to a skeptic who realized his beliefs these were deeply flawed. The aim of this series is to encourage us to admit we are fallible, can be wrong, and sometimes, we need to change our beliefs. I genuinely hope that we can learn to ask difficult questions and be unafraid of change.

Biblical studies scares all my buddies

It is impossible to underestimate the importance of the Bible to my worldview. I grew up with a traditional (sometimes called “literal”) reading of the Bible as my epistemological foundation. This means the biggest questions to life, existence, meaning, morality, teleology, and more, were directly based on the Bible (many were not based on what the text actually says, rather the idea that the text is the source). For just about any question someone could ask me, the final evidence for the answer would be “because the Bible says so.”What is right? What is wrong? Why is lying bad? Why do people die or live? What things are good? What should we do in life? What is existence? What is outside of our world?

All of these questions were answered through the epistemic framework that was built solely on a traditional reading of the Bible. At the time, if someone were to grab a hold of this biblical foundation from underneath me, and pull it out like a rug, I would fall into an existential chasm of nihilism. I would literally have no answers, for anything. I would be unable to respond to simple questions about myself like “what kind of thing am I?” The Bible was my only foundation for any kind of knowledge that could be certainly known, and I was not philosophically equipped for anything else.

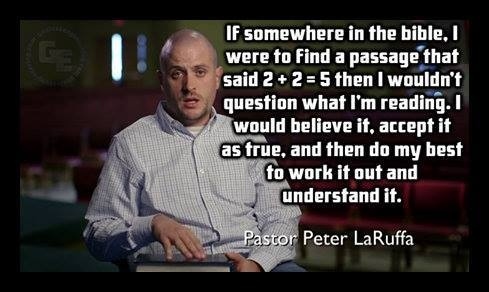

And so the Bible guided my views, even when I made radical changes. For example, as a young child I forged into the difficult-to-comprehend portions of the Bible to try to grasp at its deep hidden truths. I read the book of Revelations and tried to estimate a date for the rapture based on the fact that I believed the Bible taught this. But later I changed positions and thought that most eschatological views I grew up with were unbiblical because a more in depth reading had showed me so. This move happened because I thought the Bible said one thing, and later another, whatever the case, I would be willing to trust the Bible on anything. This picture with a quote from Pastor Peter LaRuffa during the HBO documentary Questioning Darwin is probably a pretty accurate depiction of my own former view.

Though I might have tried to argue that people just misunderstand the Bible, if there was such a 2+2=5 situation.

In retrospect I can see that my unwavering devotion to the Bible often led me on a journey of many twists and turns, a journey that would result in the loss of friendships, fortunes, and fame. The Bible led me to be a young earth creationist and a gap theorist. It made me a Pentecostal who later evolved into a charismatic only to become a cessasionist. It made me be an Arminian who became a Calvinist only to flirt around with Open Theism. It made me accept the idea of a God who would torture people for eternity, but later took me to the belief that sinners in hell would be annihilated like the biblical imagery of chaff burning in a fire.

I was willing to follow the Bible into whatever ideological direction I believed it was taking me. In fact, to the dismay of my friends, I did follow it. But I didn’t’ read every part of it with as much enthusiasm as I thought I did… and that would change everything.

It all started with the Bible

About a year and a half ago my wife motivated me to reread the Bible, and envisioning myself as the grand spiritual leader of our family I agreed that we should do another Bible reading marathon.I had read the Bible before as a teenager, twice, from beginning to end, but to be honest, at the time I had no idea what the heck any of it meant. In my later, adult spiritual development, I spent most of my time confined to only half of the book. To this day I own a few Bibles with most of the New Testament, Psalms, and Major Prophets vigorously highlighted in multiple colors. I had preached somewhere around two hundred sermons from the Bible. I had read at least two dozen theological books, written by leading conservative theologians about the what the Bible taught (including Wayne Grudems extremely thick Systematic Theology). And of course, I had spent the previous six years listening to at least one sermon a day. While most people listened to music, I listened to sermons, thousands of them. For example, during the two years I spent in clinical training for nuclear medicine, I would listen to two hour-long sermons/theology lectures a day, one on the hour-long bus commute there, and another on the way back. This was my life! To sum all of this up, I certainly thought I knew what the Bible said. In fact, I sincerely thought that there were very few people I personally knew who could top my theological and biblical knowledge. Looking back at this fact, I still think it remains mostly true, the one or two exceptions among my friends all have graduate degrees in the field.

So as I started rereading the Bible, I had a very good expectation of what was there. I knew it like the back of my hand. But this time was very different, instead of reading assorted chapters from different places, I tried to read it in one linear direction. Instead of stopping every few minutes to read commentaries that explained away strange things, I wanted to grasp a comprehensive picture of the whole process without interruptions and without other people telling me what I had just read.

Like before, each day I started off with a sincere prayer, asking eagerly “Lord show me your truths in these words, let them speak into my heart.”

And so I jumped into the Bible, enthusiastically hoping God would speak to me with his inerrant word. To make the experience more interesting than previous times, I decided to do something new and supplemented my reading by listening to an audio version of the text instead, often stopping to more closely look at a passage in the text. This time my journey only lasted about 25+ hours until I got stuck in a disillusioned rut somewhere in 2nd Chronicles.

It took me less than a month of daily reading/listening to the Old Testament to start questioning the inerrancy of the Bible.Half way through this short journey I remember the first time I said to myself “I don’t want to read the Bible anymore.” Hearing this thought scared me, it felt so foreign and sinful, but it expressed my deepest feelings. I had come to God, hoping for his word to illuminate my heart and make sense of everything, but instead I got a plethora of frightening and confusing ideas. I had read them all before, but never taken the time to consider what they really meant. As biblical scholar Paul Wiebe wrote on behalf of the American Academy of Religion “one of the enduring contributions of biblical studies in this century has been the discovery of the strangeness of the thought-forms of the biblical literature of the 'western' tradition to us.” And I had previously let that strangeness fly by, but not this time.

Drowning in the tears of a dying faith

As I continued on my journey, this time as an adult, again being reminded of what the Bible actually said, as opposed to what I had thought it said, I continued to be disillusioned and heartbroken. I spent numerous nights an eager fundamentalist “crying out to God” hoping he would answer my questions and help me understand. And I continued to barge ahead, forcing myself to gulp down large buckets of Scripture, fighting the confusion and disenchantment with each swallow. Inside my soul a battle raged, my heart fought against the biblical books that showed instances of an all-loving God commanding people to chop up small children and infants or threatening to force parents to eat their babies (Leviticus 26:29, Deuteronomy 28:53, Jeremiah 19:9, Ezekiel 5:8-10).How could a God who loves us force the death of these innocent children? How could a loving God permit people to be used as slaves, and encourage masters to beat these slaves? It wasn’t consistent with my Christianity! I wrestled against biblical texts that promoted sexual slavery, the kidnapping of women to be brides after first killing their families, or the the kidnapping of young girls who were virgins as gifts for warriors, and other horrible atrocities, all purportedly permitted by an all good, all loving God. I fought it until I simply couldn’t, and I gave up.

I wept.

I was a grown man, an amateur theologian, a preacher, a youth minister, a pastor candidate at a large mega-church. I thought I knew everything, but here I had no answers anymore, just the lament of a dying faith. I was sick to my stomach. I wanted to vomit.

It didn’t make sense. In every sermon I had heard, and the hundreds I myself preached, the Bible was an amazing compendium of writings from dozens of human authors, that came together in a perfect symphony to share one elegantly cohesive message of love. Yet the text I was reading was nothing like it should be. It was filled with putrid violence, vengeance, misogyny, the condonement of vile ceremonies and superstitions. It was riddled with hundreds of contradictions and inconsistencies, scientific inaccuracies, strangely anthropomorphic views of a God who delighted in the smells of burning flesh. I grasped at the last source of hope to me, I decided the only way to save my faith in the inerrant Bible was to read the 615 page book by Dr Norman Giesler that purportedly explains away all of these issues.I started the book, eagerly hoping to find all of the answers therein, after all, Giesler is an accepted authority by conservatives on this issue. I plowed halfway through the book finding more disenchantment on every page. Had this been a Mormon author, I would have laughed at his ridiculous verbal gymnastics. Had this been a Muslim trying to defend the inerrancy of the Koran, I would have never let him get away with such preposterous ad hoc rationalizations and contortions. But because he was a fundamentalist Bible believer, part of my tribe, I desperately wanted him to be right. I rooted for him during the first two hundred pages, even as I bit my lip, seeing each distortion and fallacy in his argument. Eventually I couldn’t take it, again I felt sick and nauseous. A few days in, somewhere past the halfway point, I closed the book with a final cringe. I looked around, and noting that there was no witnesses I said to myself “I don’t believe in the inerrancy of the Bible.” (Ironically enough a friend later told me of another person who lost faith in the Bible, precisely after reading the same book with Gieslers defense of the contradictions.)

Putting down my Bible with fear and trembling

So I put aside my presuppositions, and set out to find what Bible scholars said of the “good book.” After some research I realized that most scholars were liberals who rejected the inerrancy of the Bible, and my own journey had only mimicked that of most of the great intellectuals of the last few centuries. Some of the most important names in biblical scholarship, like Friedrich Schleiermacher , Albert Schweitzer, Rudolf Bultmann, and Paul Tillich all grew up in a staunchly conservative environment and after engaging with the biblical texts became liberals or skeptics. What I found even more ironic was that, just like me, all of these liberal scholars were the sons of very conservative protestant pastors.I jumped into historical and textual studies of the biblical texts themselves only to find something even more distressing. The early Christians didn’t have one Bible, certainly not the one I held in my hands, they had a plethora of books that they frequently passed around and copied, but there was no strict canon in the first few hundred years. In fact, even after the dates conservative pastors offer for canonization, there was plenty of biblical confusion. For example, the Codex Sinaiticus (a 4th century “bible,” that is one of our best preserved manuscripts used by most scholars today to reconstruct the New Testament) includes the epistle of Barnabas & Shepherd of Hermas right in the middle of the of the “Bible”; it also excludes many sections of Mark, Matthew, Acts, and so on. Another example, the Codex Claromontanus (6th century) excludes the books of Philippians and Hebrews, but includes Barnabas, Shepherd of Hermas, Acts of Peter, and Revelation of Peter (different than Revelation of John). But besides the fact that different groups of people used different books, there were striking differences in the books themselves. We simply don’t have the original manuscripts of the new testament , and we could only figure out what was on them by using modern sciences to try to estimate what they originally said. What we do have is a collection of thousands of fragments with at least 300,000 variations between all these different ancient manuscripts.

I learned that the “Bible” in my hands was one of many reconstructions by scholars, not a supernaturally passed down text that had never changed. We have (a) many different versions/translations based on (b) multiple different printed Greek texts, (c) based on compiling bits and pieces from thousands of different fragments/manuscripts, which contain (d) hundreds of thousands of differences called textual variants.The more I read, the more I realized that mainstream biblical scholarship confirmed all of these things I was discovering, and even more so, had been grappling with these issues for hundreds of years. The oft repeated mythical stories that warned about the dangers of higher education, which often include an enthusiastic young preacher who goes to seminary (“cemetery”) and comes back doubting everything are not so mythical. From the world famous evangelist Chuck Templeton (who preached with Billy Graham for many years) until going to Princeton to engage in Biblical Studies, to Robert Funk, the agnostic historical Jesus scholar who had been a fundamentalist in his youth, these myths are real, they are the stories of thousands of people who lost their zeal after engaging in biblical studies. As the top conservative New Testament textual scholar in America, Dan Wallace, said:

- “As remarkable as it may sound, most biblical scholars are not Christians. I don’t know the exact numbers, but my guess is that between 60% and 80% of the members of SBL (Society of Biblical Literature) do not believe that Jesus’ death paid for our sins, or that he was bodily raised from the dead.”

- Also from Dan Wallace: “In one of our annual two-day meetings about ten years ago, we got to discussing theological liberalism during lunch. Now before you think that this was a time for bashing liberals, you need to realize that most of the scholars on this committee were theologically liberal. And one of them casually mentioned that, as far as he was aware, 100% of all theological liberals came from an evangelical or fundamentalist background. I thought his numbers were a tad high since I had once met a liberal scholar who did not come from such a background. I’d give it 99%. Whether it’s 99%, 100%, or only 75%, the fact is that overwhelmingly, theological liberals do not start their academic study of the scriptures as theological liberals. They become liberal somewhere along the road.”

An unwilling and disheartened sojourner, after trying so hard to prove its veracity and failing, I reluctantly gave up my faith in the Bible.

Why did I do it? What do I have to gain?

What often hurts, as I find myself being misunderstood and harshly labeled by others is that I didn’t ask for any of this. I didn’t ask to be born into a culture that would build my epistemic foundation on the Protestant canon of the Bible. I didn’t ask for this to be ripped out from underneath me. I didn’t want to start questioning the veracity of the Bible. I didn’t eagerly set out to invent errors and contradictions for some evil personal agenda. I didn’t ask for our reality to be what it is, but against all of my deepest wishes, this is the way things are. I can’t change the facts, as much as I would like to! My desire for honesty, fairness, and truth refuses to let me to pretend otherwise. I am here as a reluctant skeptic, I did not come here willingly, but only after there was no possible way I could still justify my views and remain honest at the same time. I can’t plug back into the matrix anymore and pretend it all makes sense, because it doesn’t.Over time, the disenchanted emotion of a disillusioned young man slowly wore off and I began to move on. In the last year I spent a couple hours every day time reading books by scholars from differing sides, as well as listening to many hundreds of hours of lectures, debates, and etc. After which I stand convinced that the reason conservative biblical scholars are so few (and so loud) is because there are good reasons as to why most scholars reject conservative views of the Bible. In the meantime, I’m still reading and thinking on this issue because it fascinates me, and now I’m learning to rebuild my world from scratch, after my biblical foundation has been ripped out from under me. That said, I haven’t noticed much of a practical difference, most of the things I once considered wrong are still wrong, while I now I simply reject the biblical laws that promote murder, genocide, and violence, without trying to justify them by saying “God can do anything he wants, we deserve torture.” In fact, I’ve noticed that most of us already approach the Bible with a preconstructed moral system, and then use this personal moral system to pick and choose that which we like or to reject that which we don’t (usually by saying something silly like “oh that’s meant for a different culture.”)

So what now, where will this journey finally take me? Quite frankly, I don’t really know, but I do know that intellectual honesty is now more important than ever. I am willing to believe whatever is true, regardless of how crazy or ridiculous it is, but first I must know it is the truth. Not because some authority told me, or because someone strongly feels it is true, but because I am justified in knowing that it’s true. At this point, I don’t want to believe, I want to genuinely know.

Comments (18)